Walter Ellison

b. 1899, Eatonville, GA

Walter Ellison is best known for intimately scaled works that reveal the private lives and shared experiences of African Americans who moved to northern cities from the rural South during the Great Migration between World War I and II. Born in Eatonton, Georgia, Ellison—according to census and draft records—was a farm hand when he and his family came to Chicago in the early 1920s. He attended classes at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) and at Hull House. We don’t know who Ellison studied with, but given the similarities in style and satiric approach, it is likely that Ellison was a follower of Adrian Troy, a painter and printmaker with outspoken leftist sympathies. Ellison was employed on the Illinois Art Project of the WPA and was a founding member of the South Side Community Art Center, with a number of younger black artists, including Margaret Burroughs, Eldzier Cortor, Gordon Parks, Charles Sebree, and Charles White. By the early 1940s, Ellison’s artistic career seems to have come to a halt; he died in Chicago in 1977.

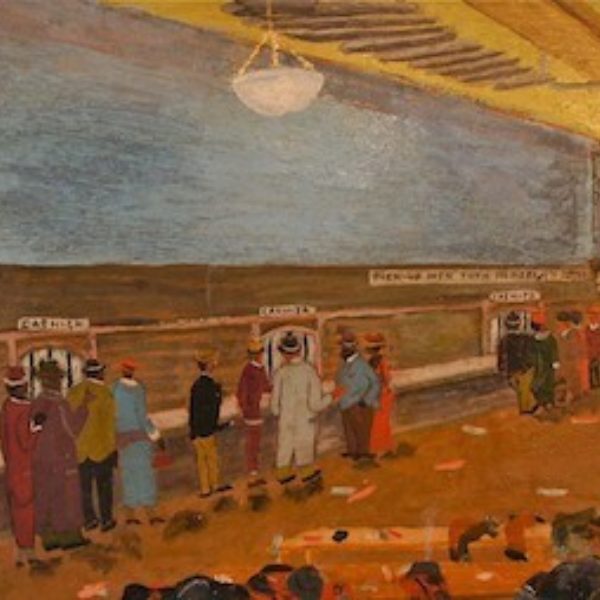

Old Policy Wheel, 1936, shows the cavernous basement of an illegal (but politically protected and syndicate-operated) Policy “station,” or numbers parlor. With the Depression raging and black unemployment at nearly 50 percent, Policy was not only an obsession, it was also one of the leading engines of jobs and economic production in Chicago’s teeming black neighborhood known as Bronzeville. As described at length by Horace Cayton and St. Clair Drake in their captivating 1945 study of Chicago’s black citizens, Black Metropolis, there were some 500 policy stations in the neighborhood: one on almost every block and more numerous than churches. At its height in the late 1930s, Policy employed more than five thousand people, “with a weekly payroll of over $25,000, and an annual gross turnover of at least $18,000,000.” An observer interviewed by Drake and Cayton described a scene that might have been illustrated by Ellison:

The station is located in the basement at an apartment building. On entering the station, you notice, to the right, a pressing shop. Along the walls are three troughlike racks with signs reading A.M., P.M., and M.N. These are the receptacles for the drawings for morning, afternoon, and midnight. These troughs have a section for every wheel for which the station writes. There are small blackboards on each side of the wall where lucky or hot numbers are placed. Each week, or every two or three days, as the case may be, advertisements of all the important wheels are placed in a conspicuous place. On a table is a large scrapbook with drawings pasted in for months past. These drawings are for reference and are often used by patrons in determining their daily plays. In the rear end of the station, behind a barred cage resembling a teller’s window, the writers are stationed. A tailor’s sign camouflages the entire station—the only sign in evidence on the outside of the building.

From a raised vantage point, as if the artist were standing on one of the long tables that people have used to deposit their scarves and topcoats—or from a window at sidewalk level—Ellison overlooks a scene of well-dressed patrons placing bets and waiting for one of the three daily drawings. At rear are the “walking writers” (those who took orders and money to the stations for clients who could not appear themselves). The tables and floor are littered with the brightly colored and discarded losing “plays.” The only human presence near the PAY-HITS window is a woman entering one of the utilitarian bathrooms at rear. Ellison’s depiction of this ordinarily cloaked scene is inventively handled, with a maximum of clarity and directness. The riot of colors of the patrons’ clothing and liveliness of incident is contrasted against the dreary and undecorated, subterranean space, painted in a ghastly blue-green hue. It suggests a will to enjoy and create despite the Depression and systemic racism that socially segregated blacks in the U.S. before World War II, even in northern cities.

The Art Institute of Chicago owns two, equally extraordinary examples of Ellison's work: Train Station, 1935, and The Sunny South, a monotype from 1939. Despite the small number of surviving works and the frustrating lack of information about his career, Walter Ellison can be considered one of the most sensitive and shrewd observers of black life in Chicago.

Daniel Schulman

References

Barnwell, Andrea D. “Walter Ellison.” In Museum Studies 24, no. 2, African Americans in Art: Selections from the Art Institute of Chicago, pp. 193–94. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1999. http://www.artic.edu/museumstudies/ms242/portfolio5.shtml.

Drake, St. Clair, and Horace R. Cayton. Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1945/1993 edition.

Koehnline Museum of Art. Convergence: Jewish and African American Artists in Depression-era Chicago. Des Plaines, IL: Oakton Community College, 2008.

Locke, Alain. The Negro in Art: A Pictorial Record of the Negro Artist and of the Negro Theme in Art. Washington, DC: Associates in Negro Folk Education, 1940; and New York: Hacker Art Books, 1940.

Schulman, Daniel. “Walter Ellison.” In Chicago Modern, 1893–1945: Pursuit of the New, edited by Elizabeth Kennedy, p. 109. Chicago: Terra Museum of American Art, 2004.