Aaron Bohrod

b. 1907, Chicago, IL - d. 1992, Madison, WI

Aaron Bohrod was born on Chicago’s West Side in 1907, the third child of Jewish immigrant parents. He gravitated toward art as a child, recalling that, at the age of nine or ten “it was fun to scribble.” After a brief attempt at training through a correspondence course, Bohrod pursued formal study at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC): initially in a Saturday morning children’s class and later, from 1926–28, as a full-time student. Both the classroom instruction and his exposure to the museum’s collection and library had significant effects on his development. During this time, Bohrod also earned a living as a commercial artist in the advertising art departments of local stores, including the discount retailer the Fair Store.

Drawn toward “the mecca for all young artists,” Bohrod relocated to New York City, where he studied at the Art Student’s League from 1929–32 with notable American artists and instructors John Sloan, Kenneth Hayes Miller, and Boardman Robinson. Bohrod credited Sloan’s insistence on humble, everyday subjects, and on “vitality in painting” as key underpinnings for his own art.

After his return to Chicago in 1932, Bohrod put Sloan’s teachings into practice by seeking out a wide range of urban locales for his paintings: “backyards and alleys and garage eaves and rooftops, and the parks, and the setting for the life of everyday people.” Working from his studio on North Avenue, Bohrod quickly established himself as a vital member of the city’s artistic community. He gathered with fellow residents and artists Francis Chapin and Davenport Griffen for sketching classes and lively discussions, embraced the “Chicago School’s” living connection to its audience, belonged to the Chicago Society of Artists, and maintained an active local exhibition schedule. He continued to take occasional courses at SAIC until 1937, and taught there briefly in the early 1940s.

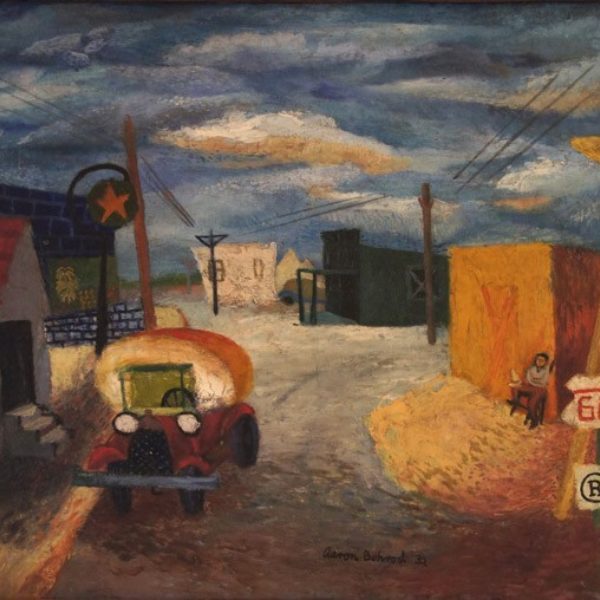

Street in Oklahoma (1932) and Burlesque at the Rialto (1935) are typical of the artist’s work from this period, and reveal his engagement both thematically and stylistically with American scene painting. In the former, Bohrod depicted a rural townscape. Although the prominent sign in the foreground marks its location along Route 66—the “Main Street of America”—the deserted road and the sinister expanse of sky convey desolation and despair. A Texaco station and a few boldly colored structures line the forlorn thoroughfare, devoid of human presence with the exception of the lone figure reclining against the building to the right. The eerie quality of the scene is emphasized by the blackened windows and doors of the buildings, the skewed perspective of the telephone poles and wires, and the white headlamps of the parked car, which stare vacantly at the viewer. Above, the roiling, darkened clouds suggest an impending storm, perhaps one of the “black blizzards” of swirling dust that ravaged the Great Plains during the 1930s. The spontaneity of the brushstrokes and loose handling of the paint further enhance the simplicity and rural character of the setting.

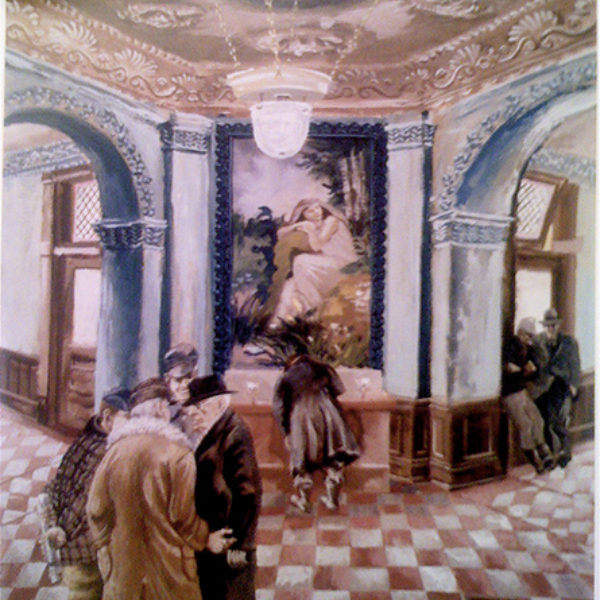

By contrast, Burlesque at the Rialto revels in a vibrant, densely populated scene of urban spectacle in a more ordered, tighter style characteristic of Bohrod’s work beginning in 1934. In the foreground, heads and shoulders of the overwhelmingly male viewers are packed into neat rows, framed by the rigid geometry of vertical stripes and arches on the left wall and the forceful beams overhead. A muted palette of grays, browns, and flesh tones suggests a murky, smoke-filled haze. Bohrod set the stage in dynamic opposition to the audience’s space: the luminous, writhing female performers create a sinuous pattern of flesh-colored arabesques against a striking blue curtain, punctuated with bursts of brilliant yellow, green, purple, and orange. The movement and bold sensuality of their nude bodies is at odds with the staid, drably garbed seated men. Bohrod’s technique is more controlled in this painting, with a greater attention to detail in the figures and architecture that is softened with a glimmering surface effect. The burlesque show enjoyed great popularity during the 1930s and served as an alluring subject for several important American artists, most notably Reginald Marsh. Bohrod’s Burlesque at the Rialto bears a striking affinity to Marsh’s numerous canvases featuring performances such as Star Burlesque (1933, Curtis Galleries, Minneapolis).

Throughout the Depression, Bohrod managed to support himself as a full-time artist. He sold a number of watercolors for up to $35 apiece through the Chicago gallery of Mrs. Increase Robinson. Robinson, who served as State Director of the Federal Art Project in Illinois between 1935 and 1938, facilitated commissions from Bohrod for three WPA murals for post offices in Clinton, Galesburg, and Vandalia, Illinois. The artist’s professional achievements in the 1930s also included two consecutive Guggenheim Fellowships (1936–37 and 1937–38), which funded trips to the West, and the South and Northeast, respectively. In 1939 Bohrod was accepted into the Associated American Artists group, whose membership included such luminaries as Grant Wood, John Steuart Curry, and Thomas Hart Benton. This New York-based gallery marketed art to the middle classes and employed artists to produce affordable lithographs during the Depression. In 1941 Bohrod was appointed a visiting artist at Southern Illinois University, a post that he vacated in 1942 to serve in the Army War Art Unit during World War II. In 1948, he was appointed artist-in-residence at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, where Bohrod remained until his retirement in 1973.

Despite his success as an American scene painter, Bohrod’s work shifted dramatically in 1953, when he abandoned the themes of his earlier work and devoted his attention to precisely detailed trompe l’oeil paintings. The artist earned recognition and praise for this new genre, and his work appeared widely in magazines, galleries, and museums over the ensuing decades.

Patricia Smith Scanlan

References

Aaron Bohrod: Early Works. Hopkins, MN: F. B. Horowitz Fine Art, 1988.

Cozzolino, Robert. “Aaron Bohrod at 100.” Wisconsin People and Ideas 53 (Fall 2007): 29–36.

———. Art in Chicago: Resisting Regionalism, Transforming Modernism. Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 2007.

Lambert, Bruce. “Aaron Bohrod, 84, Realist Artist Whose Paintings Could Deceive.” New York Times, April 6, 1992.

Oral history interview with Aaron Bohrod, Aug. 23, 1984, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-aaron-bohrod-12310.

Singer, Carole. “The Unusual and the Eerie in Aaron Bohrod’s Early Paintings: 1933–1939.” In Kathryn Whitford, ed. Transactions of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters

74 (1986): 108–21.

Weininger, Susan S. “Aaron Bohrod.” Catalogue entry in Elizabeth Kennedy, ed. Chicago Modern, 1893–1945: Pursuit of the New. Chicago: Terra Foundation for the Arts, 2004.

Artist image: Photograph of Aaron Bohrod, June 1961, collection of Bernard Friedman.