Anthony Angarola

b. 1893, Chicago, IL - d. 1929, Chicago, IL

Anthony Angarola, the seventh of the eleven children of Italian immigrants Rocco and Anna Bonomo Angarola, was born in Chicago in 1893. Although he had artistic aspirations from a young age, he had little support from his family and he worked at a series of jobs, including plumber, house painter, baker, theater usher, actor, and singer to pay for his education at the School of the Art Institute (SAIC). He began studying part-time in 1908, finally graduating in 1917. Along the way he accumulated an impressive series of honors including numerous honorable mentions in specific classes, best student of the year in 1915, and a full tuition scholarship in 1917. Although he studied with a number of people at SAIC, the most profound influence on him was the painter Harry Walcott. Angarola continued to garner awards, including the Clyde M. Carr Award at the Annual Exhibition of Artists of Chicago and Vicinity at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1921, the Silver Medal at the Chicago Society of Artists exhibition in 1925, and a Guggenheim Fellowship that allowed him to travel to Europe in 1928–1929. In addition to exhibiting regularly in the juried Art Institute Annuals in Chicago, his work was seen at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts Annuals and the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh, both national juried shows. He taught at the Layton School of Art in Milwaukee (1921), the Minneapolis School of Art (1922–25), the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (1926), and the Kansas City Art Institute (beginning 1926), where he was appointed head of the department of drawing and painting in 1927. He was a dedicated and successful teacher who took pride in his students’ achievements, as evidenced by the file of clippings and correspondence found in his papers. Shortly after returning from Italy and France to Chicago in August 1929, he died suddenly at the age of 36.

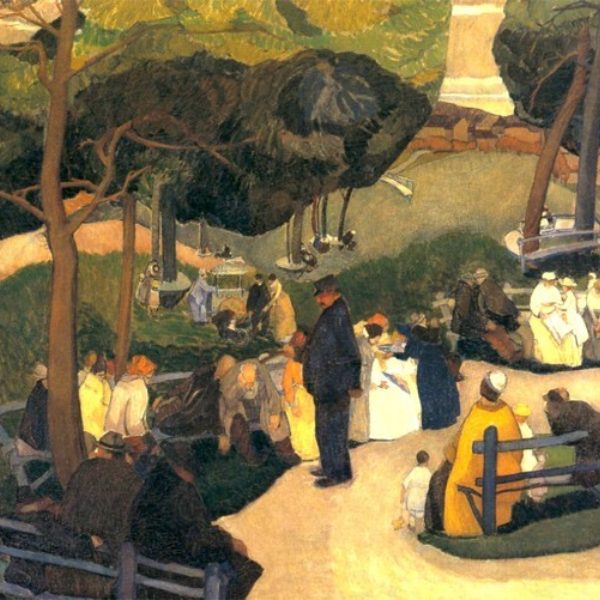

He produced paintings, prints, newspaper and book illustrations during his short career. Despite his traditional education at the School of the Art Institute, by the late teens, he was working in a variety of modes related to post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism, as we see in the monumental Bench Lizards, 1922. Along with other progressives such as William S. Schwartz and Raymond Jonson, he incorporated modernist innovations which he applied to subjects ranging from landscape and figure studies to highly imaginative and almost wholly abstract images such as In a Dentist’s Chair (1923).

Like the regionalists Thomas Hart Benton, John Steuart Curry, and Grant Wood, Angarola celebrated middle America. Unlike them, however, he was interested in the ethnic communities that flourished in Chicago, Minneapolis, and Lawrence, Kansas. Works such as Swede Hollow, Little Italy St. Paul, German Picnic, Ghetto Dwelling, and Bohemian Flats show his interest in the enclaves created by immigrants in the early part of the century, and the strengths that these groups lent to the fabric of the country. Although exalting the American heartland, Angarola did so exclusively within the parameters of a modernist vocabulary.

Like other artists who were immigrants or first-generation Americans, Angarola had great sympathy for those who found themselves outside the mainstream, and produced a number of images in which his compassion for his subjects is evident. Although this kind of imagery was popular in the period of the Great Depression, Angarola died even before the 1929 stock market crash. Images such as Proud, which represents an impoverished family in an austere interior, is even more poignant given the prosperity of some Americans in the 1920s.

Angarola was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship to study painting in Italy; he indicated on his application that he was interested in the work of proto-Renaissance figures such as Giotto, and especially Giotto’s bulky, flattened figures with their combination of figuration and abstraction. (A copy of the application is in the Angarola Papers.) Indeed, he seems to have already been moving in the direction of creating the large-scale, angular forms that are evident in works such as Judas (1928) and Snowbirds, painted just before he left for Italy. Not only does Judas foreshadow work done abroad such as Café Chauffeurs (1929), but it continues the interest that Angarola, a lapsed Catholic, had in using religious subjects to illuminate secular issues. Beginning in late 1927, Angarola was having some issues with a colleague, Andrew Kostellow, referred to in several letters in the Angarola Papers. Angarola felt that Kostellow had somehow betrayed him, in what way it is not completely clear (it is possible Kostellow did not support him in continuing in his position in Kansas City). While this is wholly conjecture, Angarola may have used the Judas figure to express his feelings of betrayal.

Susan Weininger

References

Angarola, Anthony, Papers. Smithsonian Institution. Archives of American Art.

Bulliet, C. J. “Artists of Chicago Past and Present, No. 78: Anthony Angarola.” Chicago Daily News, September 26, 1936.

Greenhouse, Wendy, and Susan Weininger. Chicago Painting 1895 to 1945: The Bridges Collection. Exh. cat. Springfield: University of Illinois Press and Illinois State Museum, 2004.

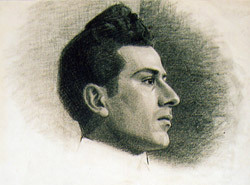

Artist image: George Josimovich, Anthony Angarola, c. 1915. Pencil on paper; 14 x 16 in. Collection of Bernard Friedman