Carl Hoeckner

b. 1883, Munich, Germany - d. 1972, Berkeley, CA

Carl Hoeckner was born in Munich in 1883, to a family with a long line of artists. His early art education began under his father, an etcher, and flourished through formal study at art academies in cities throughout Germany and in Belgium. The senior Hoeckner instilled in his son an enthusiasm for America and impressed upon him the value of commercial art as a means to finance more creative endeavors.

Carl immigrated to Chicago in 1910 and followed this advice, supporting himself as an illustrator at the Armour Meat Packing Company for four years and then at Marshall Field’s until the end of World War I. His early paintings from this period are highly decorative and richly colored, such as Salome, his first picture exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1913. Hoeckner continued to show his paintings and prints at the Art Institute in group and solo shows into the mid-1930s, winning awards in 1922 and 1923 and garnering critical notice in the press.

In the 1910s and 1920s, he allied himself with other progressive Chicago artists to do “effective pioneer work for ‘modernism.’” Hoeckner joined the Palette and Chisel Club, where he encountered like-minded practitioners Rudolph Weisenborn and Ramon Shiva. Together, they led the city’s avant-garde and initiated several anti-institutional groups and independent exhibitions. In 1921, Hoeckner, Weisenborn, and Raymond Jonson helped organize a Salon des Refusés of nearly 300 works at Rothchild’s department store on State Street. In the wake of this successful exhibition, the artists founded the Cor Ardens (Ardent Hearts), “an international brotherhood of artists which aims to hold exhibitions without juries, prizes, or sales.” In 1922, the trio, along with Shiva, formed the Chicago No-Jury Society of Artists to enable artists to show their work in non-juried exhibitions.

It was the trauma of World War I, however, that truly radicalized Hoeckner and his art. In a 1937 interview in the Chicago Daily News he recounted: “My art aims, up to the outbreak of the world war were the search for and the expression of beauty. During the war I became interested in truth—in bitter truth and the struggle of life in general.” A few months after the armistice, Hoeckner began work on his ambitious canvas The Homecoming of 1918 (1918–19), a grisly depiction of emaciated, disfigured victims of war. Described as “perhaps the most powerful indictment of war ever painted in America,” the painting elicited “an ominous stir” in the galleries of the Art Institute when it hung there in a 1920 exhibition. Hoeckner defended the gruesomeness of his and other contemporary pictures, claiming that “the moderns” are not “commercial-minded, but they are endeavoring to depict truth.”

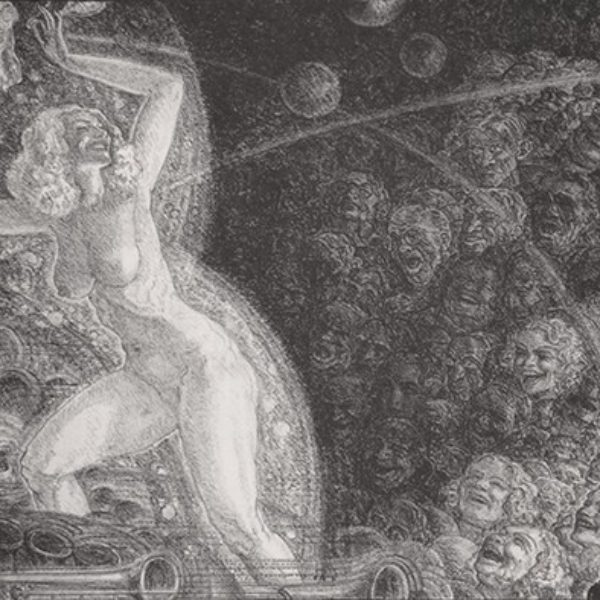

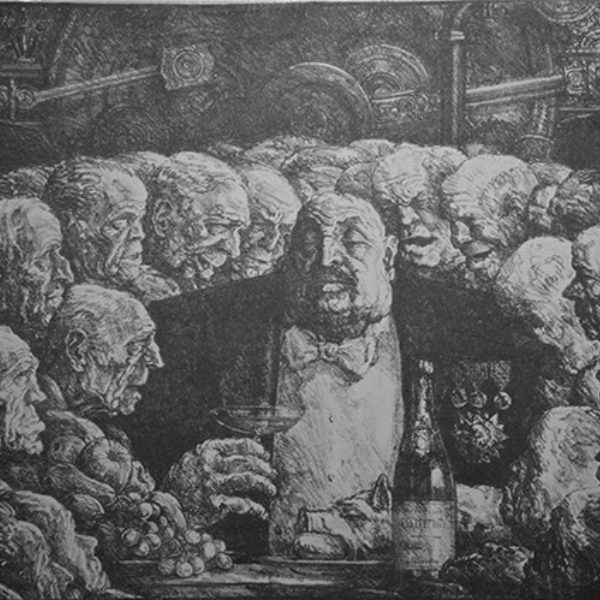

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Hoeckner created paintings and prints “representative of his emotional records caused by the world war, the steel age, and the jazz age.” His renderings, which depict “the mud swirl of industry,” the raw energy of jazz music, and the economic devastation of the Depression, were characterized as “large, vivid, drama colorings, recognizable for their suggestion of certain subterranean qualities.” In his lithographs from the 1930s, Hoeckner’s talents as a printmaker and his activism coalesced to produce “social documents” reflecting his ideals of justice. The Jazz Age and The Yes Machine (both c. 1935), both based on his paintings, expose the darker side of American society during this tumultuous era. In the former, a voluptuous female figure sways provocatively before a sea of malevolent, jeering faces while trumpets blare the improvisational rhythms of jazz. Arcs and rays of light and smoke mimic the movements of her curvaceous body. Hoeckner contrasted her pale, nude form against the shadowy throng of onlookers to denounce the sexual exploitation of women. In The Yes Machine, waxen, evanescent profiles of grossly caricatured heads wreath the hulking, corpulent frame of a well-dressed man at the center. Champagne and a roast pig—signs of his gluttony and wealth—await his consumption. Hoeckner borrowed these compositional elements from his painting of the same title, but made significant changes in the lithograph to target the injustices of industrial capitalism. He omitted the seductive nude female body and the raucous male viewers in the former in favor of a frieze-like arrangement of ashen visages, and introduced an imposing background of machine components buttressed by a pair of monolithic police officers. Commenting on these additions, Hoeckner noted: “Under Capitalism is the flattering of the boss which is common to social structures hence the title. Symbols of the boss’ power are to be found in the machinery and police protection in the background & a ‘mirror’ of himself in the stuffed pig in the foreground.”

Thematically, in its references to labor, and stylistically, through its tightly packed, repetitive forms, The Yes Machine recalls the politically charged work of the Mexican muralists of the period such as Diego Rivera. Hoeckner may have encountered Rivera’s work through fellow Chicago artist Morris Topchevsky, who studied in Mexico in the mid-1920s and produced socially conscious paintings upon his return to the city. Both artists were members of the American Artists Congress, a leftist organization formed in New York in 1936, which aimed to disseminate art to the masses through the ideal “democratic” medium of prints. At Chicago’s Hull House, Hoeckner taught alongside Topchevsky’s brother, Alex Topp, and other activist artists recently returned from stints in Mexico. As well, Hoeckner endeavored to expand the reach of fine art through his involvement in WPA initiatives: he served as director of the Graphics Division for the Illinois Art Project in the 1930s and painted WPA murals for Grant High School in Portland, Oregon, and Coonley School, Downers Grove, Illinois.

During his career, Hoeckner participated in numerous group exhibitions with the Chicago Society of Artists and Chicago Society of Etchers, and showed two of his paintings at the Century of Progress Exposition in 1933. He exhibited in other major US cities: in New York with the Society of Independent Artists (1918, 1928–29) and at the National Academy of Design (1942–43), and at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (1921). He taught at the School of the Art Institute from 1929 to 1943 to supplement his work as a fine artist. Through his teaching, original oil paintings, lithographs, and social activism, Hoeckner left behind an enduring legacy of the art scene in Chicago during the Depression.

Patricia Smith Scanlan

References

Bulliet, C. J. “Artists of Chicago, Past and Present, No. 86: Carl Hoeckner.” Chicago Daily News. July 10, 1937.

Hoeckner, Carl. Pamphlet file P-31762. Ryerson Library. Art Institute of Chicago. [28 items]

Falk, Peter Hastings, ed. The Annual Exhibition Record of the Art Institute of Chicago, 1888–1950. Madison, CT: Soundview Press, 1990.

———, ed. Who Was Who in American Art 1564–1975: 400 Years of Artists in America. Vol. 2. Madison, CT: Soundview Press, 1999.

Galpin, Amy, and Susan Weininger. “Carl Hoeckner.” In Elizabeth Kennedy, ed. Chicago Modern, 1893–1945: Pursuit of the New, 122. Exh. cat. Chicago: Terra Foundation for the Arts, 2004.

Ganz, Cheryl R., and Margaret Strobel, eds. Pots of Promise: Mexicans and Pottery at Hull-House, 1920–40. Urbana: University of Illinois Press and Jane Addams Hull-House Museum Chicago, 2004.

Mavigliano, George J., and Richard A. Lawson. The Federal Art Project in Illinois. Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 1990.

“News of Chicago Society.” Chicago Daily Tribune. November 19, 1922.

“Nine Artists to Hold Shows at Institute.” Chicago Daily Tribune. July 19, 1935.

Not a Pretty Picture: Carl Hoeckner (1883–1972): Social Realism. San Francisco: Atelier Dore, 1984.

Parmer, Dorothy. “Reds and Whites in Art.” Oak Leaves. February 17, 1923.

Simons, Hi. “American Exhibition, Art Institute, Chicago, At Chicago.” The Arts (November 1921).

Weininger, Susan S. “Modernism and Chicago Art: 1910–1940.” In The Old Guard and the Avant-Garde: Modernism in Chicago, 1910–1940, ed. Sue Ann Prince, 59–75. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

———. “‘The Spirit of Change’: Modernism in Chicago” and “Carl Hoeckner.” In Chicago Painting 1895 to 1945: The Bridges Collection. Urbana: University of Illinois Press with the Illinois State Museum, 2004.

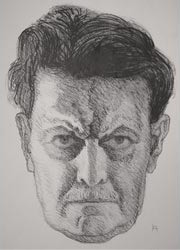

Artist image: Carl Hoeckner, Self-Portrait, 1930s. Lithograph, no. 1 of 17; 15 5/8 x 10 5/16 in. Collection of Bernard Friedman.