Frances Foy

b. 1890, Chicago, IL - d. 1963, Chicago, IL

Frances Foy was born in Chicago but raised in the suburb of Oak Park, where she pursued her first artistic activities, winning a national prize for a drawing when she was just thirteen. Her first formal training was with the conservative artist Wellington J. Reynolds, in a summer program at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts while she was still in high school. After graduation, she became a successful fashion illustrator, earning enough money to support herself, although she didn’t consider this occupation that of a real artist. She continued her fine art education in evening classes at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), studying with Reynolds, who now taught there, as well as with the New York urban realists George Bellows and Randall Davey, who were visiting instructors in 1919–20. Like many young artists, exposure to these teachers was liberating and affected Foy profoundly; along with classmates Frances Strain and Fred Biesel, Emil Armin, George Josimovich, and Gustaf Dalstrom, whom she married in 1923, she participated in the progressive movement that flourished in Chicago during the 1920s and 1930s.

Although she continued to do commercial work, she began to exhibit her work in a variety of venues in the early 1920s. She showed regularly with the independent Chicago No-Jury Society of Artists, where she also took on a leadership role, as well as in the juried annuals at the Art Institute. She was a member of The Ten, another independent exhibition group of ten artists, many of whom lived in Hyde Park. In the late 1920s she was given solo shows at Chicago Woman’s Aid, the Romany Club, and the Art Institute of Chicago (she had another solo show at the AIC in 1940) as well as receiving a gold medal from the Chicago Society of Artists. She also garnered a number of awards in annual exhibitions at the Art Institute in the early 1930s. In 1928, she and Dalstrom, along with their artist-friends Frances Strain and Fred Biesel, and Hazel and Vin Hannell took a working trip to Europe, where Foy was exposed to the European modernists firsthand. Despite this, she maintained a strong connection to the representational world, and considered subject matter of utmost importance in her work, stating: “I use whatever I have of knowledge and skill and feeling to portray the subject the way I see it. As long as any artistic quality—color, rhythm, abstract form—furthers this portrayal, I consider it good.”

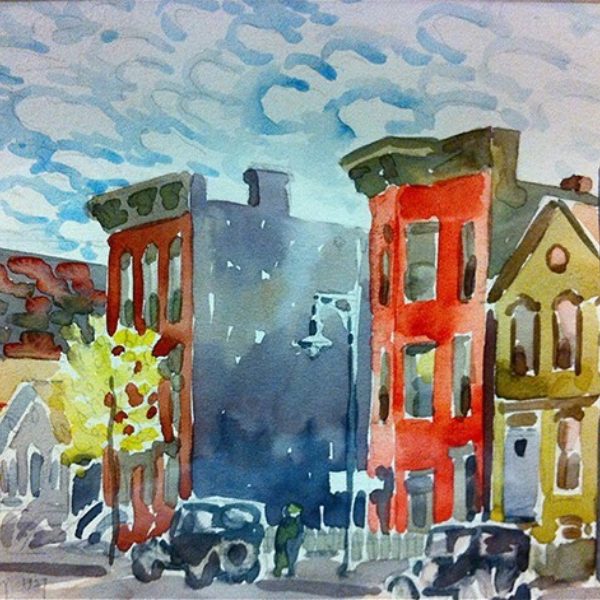

The couple settled in the Lincoln Park area of Chicago, just north of Old Town, where they often painted scenes of community life including the park and its zoo and the neighborhood children in the schoolyard, which was visible from their second-floor, home studio. The delicate and brightly colored streetscape in the Untitled (Street view) depicts this neighborhood of Victorian homes with an immediacy and mastery characteristic of Foy’s watercolors. Foy was better known for her portraits and still lifes, but was always interested in the ordinary things she saw around her, investing them with richness and life.

In addition to Foy’s other accomplishments, she was awarded five mural commissions by the Treasury Section of Fine Arts, the government agency that oversaw federal projects—primarily Post Office decorations—during the New Deal. Unlike the Federal Art Project (FAP), these commissions were not based on need but were competitive, relatively lucrative, and highly sought after. Foy was disqualified from work on the FAP, since only one member of a married couple was allowed to participate and, as was the case in most families during this period, Dalstrom received the appointment to the project.

Foy and Dalstrom learned etching at Hull House where they had the use of a press, and were both members of the Chicago Society of Etchers. Foy’s Remembered Corner, an image of a Victorian table topped with a vase of flowers and a family picture in an ornate frame, is rendered with her characteristic delicacy and technical proficiency. The profusion of patterns, from the carpet and wallpaper to the lace edging on the fabric covering the table, the curtains, the elaborate wood work on the table, and the decorative chair that can be seen through the window combine to give a feeling of warmth, complexity, and animation in this unoccupied room. Despite the fact that Foy had a successful lifelong career, this image, like much of her work, exalts the domestic sphere and its “feminine” qualities.

Susan Weininger

References

Bulliet , C. J. “Artists of Chicago Past and Present No. 27: Frances Foy.” Chicago Daily News, August 24, 1935.

Foy, Frances. “Statement.” In J. Z. Jacobson. Art of Today: Chicago, 1933, 64. Chicago: L. M. Stein, 1932.

Greenhouse, Wendy, and Susan Weininger. Chicago Painting 1895–1945: The Bridges

Collection. Exh. cat. Springfield: University of Illinois Press and Illinois State Museum, 2004.

Weininger, Susan. “Frances Foy.” In Chicago Modern, 1893–1945: The Pursuit of the New. Edited by Elizabeth Kennedy, 111. Chicago: Terra Museum of American Art, 2004.

Artist image: Frances Foy, passport photo, 1922.