Stanislaw Szukalski

b. 1893, Warta, Poland - d. 1987, Burbank, CA

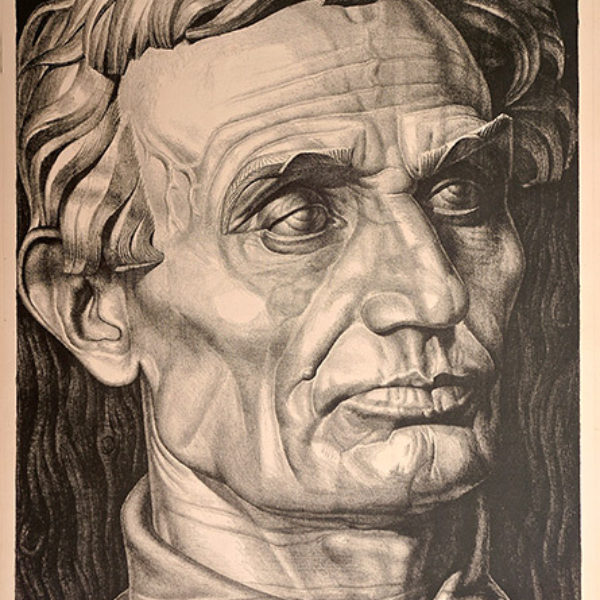

Stanislaus Szukalski was born in Poland, and took pride in his origins, asserting that “I am a Pole—that fact summarizes most of my ‘biography’.” Szukalski arrived in Chicago in 1913, having studied at the Kracow Academy where he was trained in the traditional manner and developed a refined, technically masterful, figurative style. He quickly gained a reputation as a bohemian artist, a role he relished and cultivated; his anarchic proclamations, rebellious nature, and insistent nonconformity to rules became a model for other progressives in the city. He studied briefly at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), but dropped out because “they had nothing to teach him.” Despite his years of art school training, he insisted that he was his own teacher, relying on his imagination and suspicious of any authority. He stayed in Chicago for eleven years before returning to Poland in 1924 with much of his work, most of which was destroyed by allied bombs during World War II.

In many ways, Szukalski embodied modernism in Chicago, combining its admiration for polished technique and readable, figural imagery with a rebellion against authority and attacks on the sacred cows of art history and pedagogy. It is easy to understand his appeal to both young artists and to the traditional academy. In fact, he was given two solo exhibitions at the Art Institute of Chicago, in 1916 and 1917, as well as one at the progressive Arts Club in 1919; he exhibited regularly in the juried annuals at the Art Institute as well. He was often praised by conservative critics who appreciated his refined workmanship, understanding that his life was far more radical than his art. In addition to painting, drawing, and sculpture, Szukalski wrote a number of books in which he set out his philosophy of individual expression, freedom from authority, and the primacy of the imagination, often citing the importance of drawing on one’s primitive ethnic identity for authentic expression.

Settling in California when he returned to the United States, he continued to make art and promote himself relentlessly, writing a number of books that become increasingly shrill. He had a number of loyal admirers who continue to promote his work.

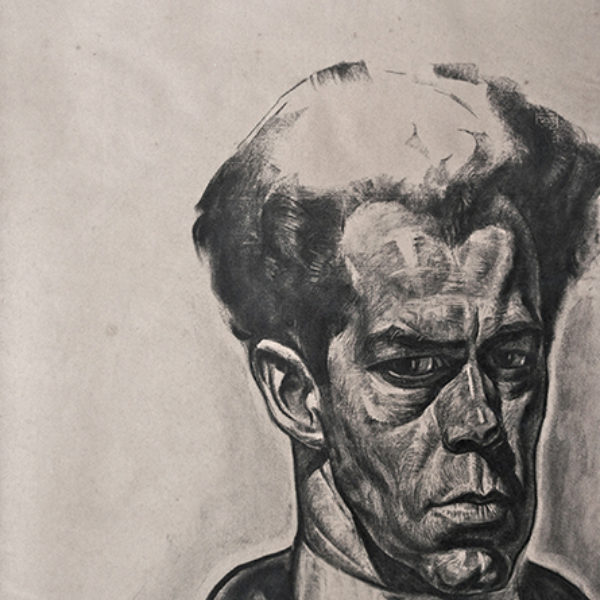

Much of Szukalski’s work is highly imaginative, using some of the methods that would later be employed by the Surrealists, such as distortions of size and shape and unusual juxtapositions of objects. In the portrait of Rudolph Weisenborn, however, Szukalski’s virtuoso technique is evident in a straightforward representation of his artist friend. Weisenborn’s head is placed to the right side of the composition, leaving a large empty space on the left, a compositional device that Weisenborn himself adopted in the numerous portrait drawings that he produced in the 1920s. According to contemporary reports, Szukalski “forced Weisenborn to sit for him in a cold room from 2 a.m. till morning and Weisenborn loved the completed picture.” Weisenborn is represented in the guise of a monk, presumably to suggest his role as the visionary artist who will aid, in Szukalski’s words, in the “making of a new civilization.” It is fortunate that the drawing remained with Weisenborn and escaped the fate of the rest of Szukalski’s two-dimensional oeuvre, all of which was destroyed in World War II.

Susan Weininger

*There is some dispute regarding Szukalski’s birth date. I have used the date cited in the Art Institute of Chicago records. Other sources list 1893 as his birthdate.

References

Gambon, Blanche. “Stanislaw Szukalski: Painter, Sculptor, Architect, Philosopher.” The New American (September, 1935), n.p.

Linn, James Webber. “Chicago Byways and Highways,” Chicago Herald and…[cut off] (18 August 1923). Rudolph Weisenborn Papers. Archives of American Art, Washington, DC, roll 856, frame 1189.

Szukalski, Stanislaus. Projects in Design. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1929.

Szukalski, Stanislaus. The Work of Szukalski. Chicago: Covici-McGee, 1923.

Weininger, Susan. “Modernism and Chicago Art.” In The Old Guard and the Avant-Garde, edited by Sue Ann Prince, 59–75. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

Weininger, Susan S. “Fantasy in Chicago Painting: ‘Real ‘Crazy,’ Real Personal, and Real Real’” and “Stanislaus Szukalski.” In Chicago Modern, 1893–1945: Pursuit of the New, edited by Elizabeth Kennedy, 67–78; 155. Chicago: Terra Museum of American Art, 2004.

Artist Image: Stanisław Szukalski in Kraków, 1936 / photographer unidentified. Koncern Ilustrowany Kurier Codzienny (Wikimedia Commons).