Thelma Johnson Streat

b. 1911, Yakima, WA - d. 1959, Los Angeles, CA

Born in 1911 in Yakima, Washington, Thelma Johnson Streat spent much of her childhood in cities in Oregon and Idaho. These early years had a profound and lasting influence upon Streat’s artistic practices and production. Driven by a sense of pride in her family’s African American identity and a fascination with the rich indigenous traditions of the Northwest, Streat held a lifelong commitment to forging cross-cultural influences in her work. Streat displayed a prodigious talent from a young age: she began painting at seven and, at the age of seventeen, exhibited with the Oregon Federation of Colored Women and at a Harmon Foundation Exhibition in New York, where she won an Honorable Mention for her painting A Priest. After graduation from Washington High School in Portland in 1932, Streat embarked on a career as a professional artist and pursued additional training at the Art Museum School in Portland (1934-35) and at the University of Oregon in Eugene (1935-36). She exhibited her early work—mostly portraiture and representational in style—frequently at local venues and in a second Harmon Foundation exhibition at the New York Public Library. Her first major success as a professional artist came with the sale of four paintings to the famous African American singer, Roland Hayes.

Thelma married Romaine Virgil Streat in 1935; in 1938 the couple moved to San Francisco, where Thelma worked with the WPA alongside sculptor Sargent Johnson and Ruben Kadish. In the late 1930s, Streat began to receive attention on a national level from showings of her work at galleries in Portland and San Francisco and at the San Francisco Museum of Art, as well as in African American exhibitions including the American Negro Exposition in Chicago in 1940. That same year she participated in the interactive exhibit Art in Action at the Golden Gate International Exposition, where she assisted muralist Diego Rivera with the Pan-American Unity mural. Streat’s contact with Rivera was a further catalyst for her interest in and, ultimately, her standard for multiculturalism that lasted throughout her career. Exhibitions of her works at Stendahl Galleries in Los Angeles (1940), the M.H. de Young Museum in San Francisco (1941), the Raymond & Raymond Gallery in New York (1942), the Art Institute of Chicago (1943), and the influential Little Gallery in Los Angeles, owned by actor Vincent Price (1943), resulted in increased visibility, critical recognition, and sales of her works. In 1942, Streat became the first African American woman to have a painting purchased by the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The painting, Rabbit Man, reveals the convergence of influences on Streat’s work in its abstracted symbolic imagery, stylistic elements drawn from Northwest Coast indigenous art, and African American facial features. At a time when many American painters were turning to European modernism and African art for inspiration, Streat’s incorporation of elements from African, Mexican, and Canadian artists distinguished her.

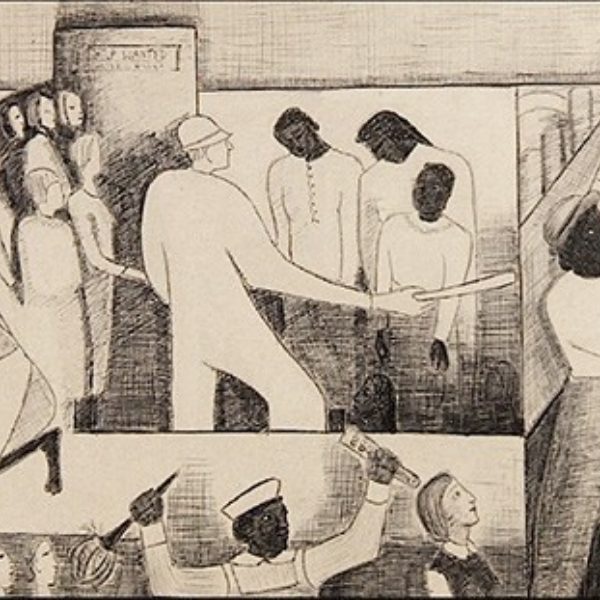

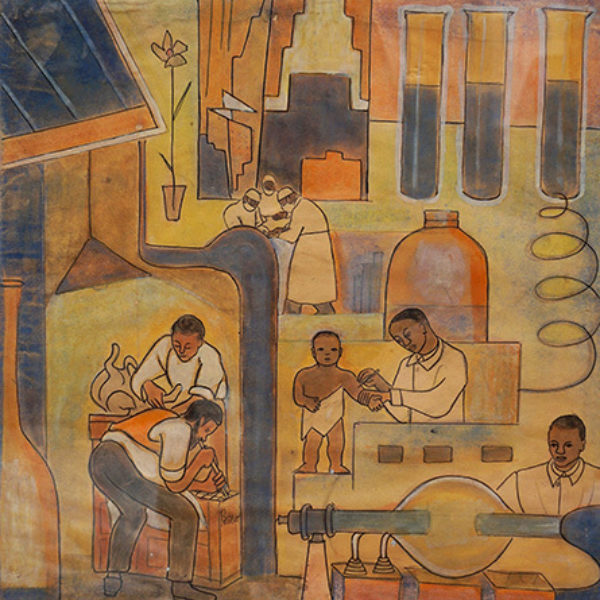

Around 1944 Streat left California and settled in Chicago, where she taught art and worked on a number of mural designs of African Americans. After receiving threats from the Ku Klux Klan for the display of her controversial mural Death of a Black Sailor in Los Angeles in 1943, Streat changed her approach and began a series of murals illustrating the positive contributions of African Americans to education and industry. The studies for The Negro in Professional Life in the Friedman Collection feature scenes of African Americans hard at work in a variety of jobs and fields of employment. In the three ink and graphite studies—The Meatpacking Industry, The Railroads, and Women in Work—Streat highlights differences of race and power in the workplace by juxtaposing the figures of laboring but subservient African American men and women with the exaggerated giant figures of their white “superiors.” One of the few challengers to this hierarchy is the female figure in the foreground of Women in Work: facing out toward the viewer, she raises her hands almost in a gesture of victory while clutching a paper inscribed with “8802,” a reference to the executive order issued in 1941 prohibiting discrimination in the defense industry. In the watercolor study The Negro’s Contribution to Medicine and Veterinary Science, by contrast, dignified African American doctors and scientists assume prominence in the composition as testament to their educational and professional advancements in these fields. Streat entered Women in Work in a competition at Chicago’s Southside Community Art Center, where it tied for first prize with William Carter. Streat and Carter were asked to submit new designs and the outright winner would be decided at a later date. Streat went on to execute several mural designs and even “mini-murals” (over-sized studio works averaging 30x60 inches but painted in a mural format). As chairman of the Negro Labor Murals Committee, headquartered in Chicago, as well as the Children’s Visual Education Project, Streat planned to translate her studies of The Negro in Professional Life into twelve large murals measuring three by six feet, as well as into prints that could be distributed easily to schools and libraries throughout the country. By 1945, three murals had been sponsored: the first, by a New York City group; the second, by a Chicago group (depicting meatpacking); and the third, by a Portland group. Although there were no details given about the identities of these “groups,” they most likely comprised individual patrons and supporters in those specific cities. An article published in The Chicago Defender in 1945 reports that Streat had returned to the West Coast for the summer, but planned to return to Chicago that autumn to continue her work on the mural projects.

In the summer of 1945, Streat’s mural The Negro Woman in Industry was exhibited in the lobby of the Portland Civic Center and accompanied by a dance presentation by the artist. A series of groundbreaking performances followed at museums and other venues around the country, including at the Museum of Modern Art, where she danced before one of her large, abstract paintings. Streat’s decision to supplement her two-dimensional art with movement and sound was clearly an effective one and was used in a very similar way to in which artists today market themselves simultaneously with their artwork. Her artwork became much more provocative because it engaged the viewer. Streat drew upon traditions from diverse cultures in both her performances and paintings in order to make her art more accessible and completely universal.

After her divorce from Romaine Streat in 1948 and subsequent marriage that same year to her manager, Edgar Kline, Streat and her second husband traveled throughout the U.S., Canada, Mexico, and Europe, where she performed for live audiences and televised programs. Following their world tour, the couple pursued their commitment to education by opening schools in Hawaii and British Columbia to teach multiculturalism to children. Streat continued her own studies of diverse cultures until the end of her life: she had recently begun to study anthropology at UCLA before her untimely death in Los Angeles at the age of 47.